Executive Summary: Dr. Rick was in Gondar and unexpectedly met a patient with a severe spine deformity.

by Rick Hodes, MD

I just took a late night walk around my home. My sons were asleep in their bedroom. In the living room, the scene is a bit different from usual. On the sofa against the window is Yilak, a shoe shine boy with a twisted spine from polio. After recent scoliosis surgery in Ghana, he gained over 6 inches in height. In a few weeks, he will be strong enough to return to his brother’s home.

Tesfaye, an Agaw boy from Gojjam, is asleep as well. Tesfaye’s back is shaped like a dinosaur. I am working to send him abroad for surgery.

Tihune, 14, has recovered most of the neurologic function lost during her scoliosis surgery. She has the sofa against the wall.

But there are 2 new shapes on a mattress on the floor, who arrived hours ago. It's miraculous.

Bear with me while I share with you the mundane details of a couple of days. I slept for 3 hours on Sunday night, 2 Sept, before leaving my home at 4:30AM for the domestic side of Bole Airport in Addis Ababa. After I arrived in Gondar a few hours later, I saw patients and did paperwork. Our JDC clinic there cares for several thousand potential immigrants to Israel.

Gondar is a small city of 130,000. It feels more like a large African village than a major city. It was laid out by the Italians during their occupation of Ethiopia in the 1930s. The main buildings are built of yellow concrete, in Italian rectangular style. The post office, overlooking the main traffic circle, looks onto the main street, which has a row of palm trees in the middle, leading to the 15th century stone castle of King Fasil, a kilometer away. Coffee shops, juice bars, and small tourist shops abound.

There is nothing fancy about Gondar, but it is authentic Ethiopia. Orthodox churches thrive, as well as some Catholic and now Protestant. There are several mosques. Over the years, internet cafes have sprung up and recently, the first ethnic restaurant opened on the main street. It is Italian, with a fashionable silver sign reading: "Tuscany." I’ve tried it: overboiled pasta with overcooked sauce. You’ve been warned.

Monday night, I napped for 90 minutes, then woke up and dug into our nutrition data. By the morning, I had finished looking at the weights and lengths of several hundred kids of our nutrition program, discharged some, leaving some unchanged, and making recommendations to change the diet of others.

Tuesday began by stopping downtown with a visiting American film team for fruit juice at SAFA juice downtown. Without asking the price, I handed them a 50 birr note (just over $5) and got 26 birr change. I calculated - that's 6 birr (66 cents US) a drink. That would be expensive in Addis Ababa, and Gondar is poorer and cheaper than Addis. Speaking colloquial Amharic, I asked the price of a juice. The waiter replied "amist birr," 5 birr. I looked down at my change. He realized that I understood I’d been overcharged, and gave me an additional 4 birr change. This still seemed too expensive.

I asked an older gentleman sitting in the corner how much he paid for juice. "Arat birr," he replied quietly, "4 birr." I raised my voice and yelled in Amharic "Hay, 5 minutes ago the juice cost 6 birr. Then it went down to 5 birr. Now I hear 4 birr - "Enante leboch nachu," "You are thieves." The word for thief, leba, is especially strong. A uniformed soldier drinking juice smiled and nodded. A European couple in the corner took note of this. The waiter silently handed me another 4 birr, and we walked out.

I sat in the office all day, seeing patients, doing paperwork and analyzing our monthly data. My lunch was the same lentil soup we feed our malnourished kids. I pondered my scheduled return to Addis Ababa the following day. I had finished what I had planned. However, I learn a lot by sitting in the clinic, and had nothing pressing in Addis Ababa. It seemed best to stay for another day. I went to the airline office downtown, and scheduled my departure for Thursday.

Late Tuesday, I was downtown in Gondar with Tesh, a 15 year old from Sidamo, who is part of my Ethiopian family. A nascent filmmaker, he was in Gondar helping the American film team produce a documentary on the upcoming Ethiopian millennium. The Ethiopian calendar, based on the ancient Egyptian calendar, begins the year 2000 on September 12, 2007. Tomorrow.

Tesh and I then ended up in town. We checked our emails - it costs 3 US cents/minute on slow, dial-up connections. He went to Facebook. We stopped to drink coffee and fruit juice at Delicious Pastry. As we walked out of the coffee shop at dusk, we ran into Tilahun Molla.

I've known Tilahun for years. He is a thin fellow, 30 or 35 years old. He is always smiling, always a bit disheveled. His bodily hygiene could use improvement. He has marginal intelligence. He is frequently teased by local streetboys, but never perturbed. I believe that he is incapable of sin. He might be what Tolstoy calls “an angel in disguise.” Whenever I ask, he tells me that he lives alone; with no living relatives. He could easily beg on the street, but instead, he supports himself by selling soap and plastic plates and individual packets of tissue to passers-by.

I had not seen Tilahun for over 6 months. Whenever I run into him, I buy whatever merchandise he has. I'm his best customer. Sometimes I spend $50, paying much more than the going price for his goods. "Let him have a good day," I tell myself. Tuesday evening he had little to sell. I bought him juice, and told him I'd meet him at 5PM at the coffee shop the next day. I gave him 100 birr, and said I'd buy whatever he came up with. He reminded me that he had 50 birr of mine leftover from 6 months before as well. At that time, he was unable to meet me, so he held onto the money for later. I was impressed; I had not expected to recover that money.

On Wednesday, I got up at 6:30, took a shower, (hot water runs for an hour in the morning and again in the evening), had oatmeal and coffee for breakfast, then walked down the hill to the city center, 2 miles away. On a good day, I can get online at an internet café before going to work, and save time. I tried checking internet in 3 different places. The normally slow dialup connections were not moving. I gave up in frustration. As I stepped out, I ran into our driver and drove with him to the office, stopping to buy bread (hand-made rolls in an old brick oven Italian bakery for 6 cents each) and a liter of bottled water for 50 cents. I was able to get online at our clinic, checked messages, saw a few walk-in patients.

Around 4:30, as the staff was departing, I left my bags and computer with our driver, then headed to town by foot, as I listened to Handel's Messiah on my ipod. I walked up the road to a bridge over the swollen river, crossed into town, and meandered up. It was 5PM, I was on time for my appointment with Tilahun.

In the pastry shop, I asked what kind of juice they had. "Ananas, papaya, avocado," they replied, the first word meaning pineapple. I ordered a mixed juice, along with a tea with lemon. And "fasting pastry," which has a filling of spinach. On Wednesdays and Fridays, Ethiopians "fast" - tsom in Amharic, meaning that they're vegans. Cafes and restaurants are filled with oxymoronic "fastingfood."

When my juice came, it had no papaya. "Alqual," the waiter said when I asked, "it's finished." The idea that the customer should be informed did not occur to him. I chuckled. There's no point complaining. There is an expressive Amharic phrase: errie bekentu, which translates as "crying for nothing."

I took my time. I was waiting for Tilahun to show up with my soap. He was meeting me for his biggest sale of the year, but he still had no sense of time. By 5:40, Tilahun had not shown up, so I paid my bill, less than a dollar, and stepped out.

While walking out, I ran into Tilahun, arriving with a carton of B-29 laundry soap, a large bag of tissues, and gella samuna, - body soap. I took Tilahun into the coffee shop and ordered him juice and coffee. I asked if he'd like cake. "Sure," he said. "Zare tsom alleh?" I asked, "are you fasting today?" "Of course," he replied, "it's Wednesday." I motioned to the waiter that I'd cover the bill, told Tilahun I'd be back soon. Once again, I headed to the internet storefront with a half dozen computers, a few doors up the block.

****

Zemene and her uncle, Menormelkam

Zemenework ("Golden Time") Tiget Adebabay is a small girl around 10 years age from rural Gondar, a region called Belessa. Her remote village has 4 huts with mud walls and grass roofs.

At the age of 2, she could not walk. Her mother took her to the town of Addis Zemen, where she was diagnosed with tuberculosis of the spine. Many think of tuberculosis as a lung disease. That’s correct, but TB can affect virtually any organ of the body. TB can twist the spine, creating angles over 120 degrees, and lead to paralysis. Zemenework took TB meds for 6 months. (TB of the bone and joint should be treated for at least 8 months). She began to stand and then to walk. Her meds were interrupted when her mother died of "bicha woba," loosely translated as "yellow fever." It could also be malaria with jaundice. Or perhaps relapsing fever, a spirochetal disease, of which Ethiopia is the world's capital. At that point, her father rejected her, and she was taken in by her grandparents. Her grandmother is now in her late 50's, her grandfather is in his 70's. She occasionally leaves her village to go to an area nearby called Hamuset. She had never been to Gondar, a full day away.

As she grew, she was smaller than other kids, and far-more frail. Her back is deformed, with a hump in the middle. Her back gets worse every year. Kids make fun of her because of her deformity.

She goes to school, she just finished 4th grade. As her uncle explained to me, "in the countryside, schools are lousy. There are 100 kids in the grade, everyone passes. But she is #4 in her class. That is worth something."

Her uncle is a 21-year old 9th grade student named Menormelkam ("Living is good.") He hails from the same village. Zemenework's late mom was Menormelkam's older sister. Menor goes to boarding school in Kuyera, outside Shashemane, in the south of Ethiopia. He's been there 3 years. He works in the school garden to pay his school fees. He also works for his relatives - 8 hours a day in the summer, and for several hours every day after school during the year. When he finishes school, he wants to study law.

Because of his poor education in rural Gondar, his English is deficient. His life is very challenging - working, going to school, and learning English. His school fee is 1500 birr per year - $166 at the current rate. Add another 500 birr ($55) for books and supplies, and he has to raise over $200 per year. That is over a years income to an Ethiopian peasant. He had no money, and had not visited his family for 3 yrs. He had hopes that a woman he met would pay his tuition, but she had not appeared at the start of the summer. In any case, concerned about his aging parents, he returned to his village for the first time in 3 years to visit his family.

His parents were thrilled to see him. "They are old, they are farmers. They have lost 5 kids," he told me, "I'm their only living son". He explained to them that he has to return to Shashemane, to school and to work. He was worried because he needs to come up with his school fees. His mother was crying. She wanted to help her son, but that was impossible.

I asked how much money the family made each year. "We don't make money," he replied, but they produce 5 quintiles of grain a year, about 1200 lbs. He estimated that it's worth 1000 birr, about $111.

Menormalkam's surviving sib is his sister, who lives in his village with her husband and 4 kids. Menormelkam's parents give them 500 birr a year. That means they have very little left for themselves, and nothing for Menormelkam.

That summer, Menormelkam noted that Zemene's back was far-more twisted than last time he had seen her. And she had grown very little. Before returning to boarding school, Menormelkam wanted to make a trip to Gondar, for the first time in his life, to bring his niece to the university hospital.

The government gives money to the residents of those villages - 50 birr per person each year. The 3 people in Zemenework's family received 150 birr, about $16. This government handout was precious, and Menormelkam wanted to use it well.

The 9 hour bus to Gondar cost 30 birr. Zemenework sat on his lap, and did not have to pay. They had great hopes. They knew people who had been cured in Gondar. Menormelkam told Zemenework: "don't worry, you'll soon be better."

Upon arrival, they were amazed by the size of the city, the people, the cars, the donkeys, horse-drawn taxis and auto taxis, and the concrete buildings of 2 and 3 floors. Zemene looked around and said "Gondar is really beautiful." They took a shared taxi to the hospital. In the hospital they got a registration card. They have a "free paper" from the local peasant association, affirming their poverty, so treatment was without cost. They were given an appointment the following day. Menormelkam phoned Selenat, a relative attending Gondar University. She came and helped them get a hotel. This turned into more of an adventure.

In the piazza area downtown, they found a hotel with rooms for 30 birr, about $3. They planned on sleeping together, paying for 1 bed. However, once the hotel staff saw Zemenework, they suddenly announced that they were full. Being small and deformed, they assumed she was sick, and they did not want her. Selenat led them to a different hotel. Menormelkam took off his undershirt and put it onto Zemenework, making her look less thin. That ploy was successful, and they got a bed for 30 birr.

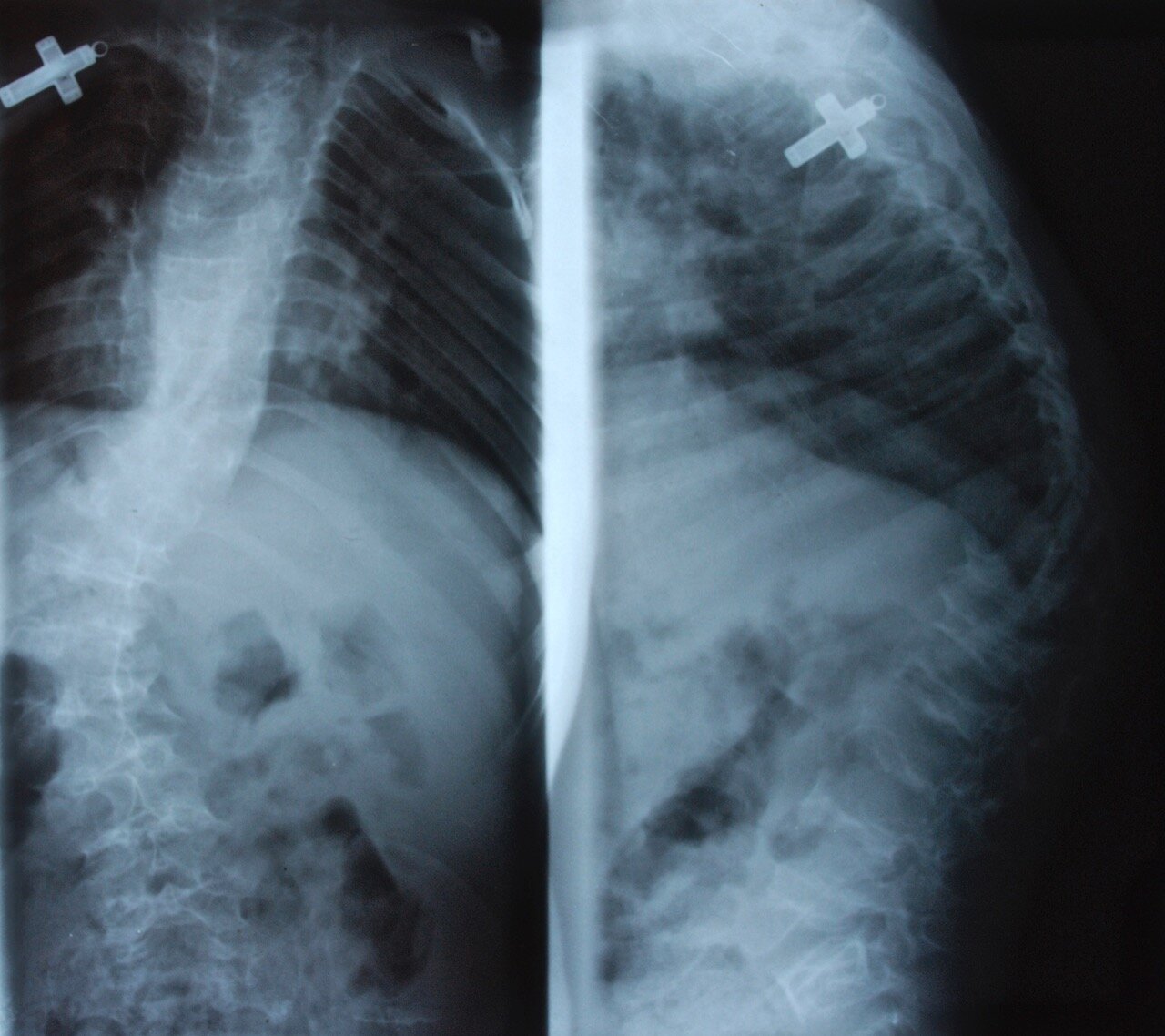

On Tuesday, they were evaluated by medical students and doctors in the outpatient clinic. One doctor said that perhaps they could squeeze her in a certain way and her back would become straight. Another said they could give a pill, and this would straighten the spine. Another said that there was an easy operation to help. Zemenework asked: "are they going to cut my body?" She was very afraid. However, they were happy and hopeful that she would become well. They waited and got their x-ray.

On Wednesday morning, they ate breakfast at the hospital: injera, the local spongy pancake made of the grain teff, with kai wat, spicy red bean sauce. In order to save money, they got 1 meal and shared it. This cost was 5 birr, just over a half dollar.

They waited all day for their doctor. They met him at 4PM. "What kind of doctor?" I asked. They have no idea. The doctor took a look at their x-ray, showed it to another doctor. They announced that there was nothing that could be done; "it's far too late." The previous day they had given her great hope - pills, squeezing, surgery. Now - nothing. “Nothing anywhere in the world,” they were advised. The doctor whispered to Menormeklam "But tell her she'll be fine."

When Menormelkam heard nothing could be done, he started crying, and Zemenework started crying as well. They walked out into a courtyard. Words cannot describe how terrible he felt. He had gone from great hope to the bottom of the bottom, in minutes. He was thinking that the family is hopelessly poor and Zemenework is the only one to help his grandparents. They have trachoma, their eyelashes grow inside and scratch the eye, Zemenework pulls out their lashes using tweezers. He thought about the taunts she gets every day when she goes to school; kids to tease her and call her gobata, bent. She would break down and cry.

He felt frustrated because he was so powerless. At this moment, Zemenwork looked up and said "I'm never going to be cured, I have to live like this."

Menor pondered her future - nobody will marry her, she'll be crippled in the countryside, and when her grandparents die she'll be all alone." The doctors' words reverberated in his mind: "there is no hope. No hope. No hope." That's pretty definitive.

At this moment, Zemene stopped crying for a moment and asked "can I go to Addis Ababa and get cured?" Menormelkam replied that he will send the x-ray to Addis and the doctors will tell us. If they can help, we'll get you there." He was making that up.

He told himself: "there's no way to get her cured. Her life is finished." "So, at that point, what did you do?" I asked. "I prayed," he answered. "In the bible, there it is a written about one lady who has a bad back, and God cured her. He said "Lord, if you did this good thing to the woman in the bible, please do this for my niece Zemenework." "It was like a dream," he said.

As they sat crying, people around commented: "it's OK, don't cry, it's God's will, you can't do anything about it." Lots of people said that. Menormelkam cried for nearly an hour. Zemenework cried longer. Menormelkam tried stopping her: "I cried because the doctor made me angry, not due to your situation. You need to stop crying."

Menormelkam thought about all the money they had spent, how they could have used it to buy shoes for his sister's barefoot kids, and instead they wasted it in Gondar, staying in hotels, sharing single meals in cheap restaurants, and searching for non-existent medical care. He never felt so bad in his life.

They went to a kiosk, phoned Selenat and told her "Forget it, there is no hope." She said "OK, I'll come and say goodbye." Then they went into town by taxi. They got a cheap hotel room by the bus station, so that they could leave early in the morning for their village. The bus station is about a half hour from the center of the town. They decided to walk downtown with Selenat.

The moment they were walking in front of the souvenir shop next to Delicious Pastry, I stepped out. We were going in opposite directions. Right in front of me, I saw a young man with a small girl who had a twisted spine. We almost collided.

In 1990, I did not recognize my first TB spine patient. My Ethiopian GP brought the patient into my office and said: "Dr. Rick, what's the diagnosis?" Looking from the front for a full 20 seconds, answered "To me he's fine." His long legs and short torso and raised shoulders did not register. Now I pick these up in a split second, from any angle. TB spines are part of my daily life.

I stopped Menormelkam and said in Amharic "She has a bad back, no?" "Yes," he said, "Terrible spine. And the doctors here say it is hopeless."

"Listen," I said, "Ene jerba hakim" - "I'm a spine doctor. I treat people like this," I said, "sometimes I can send them abroad for surgery."

Later I asked him "When I spoke to you, what did you think?” He had seen a farenge, a white person before. Zemenework had not. He was afraid, but thought I might give some help, or donate money.

I took her into the corner of the internet café to examine her. She was facing me, about up to my waist. When I pulled up her dress to see her back, I saw that she was not wearing underwear. I wanted to give her privacy, not undress her in front of strangers.

I explained that we could all go back to my hotel room and I could examine her in privacy. I phoned Tesh and said “you may want to film; I just ran into a spine patient.” We hailed a taxi. On exam, I noted that she was very small, extremely thin, and her back was twisted, more prominent on the left. Her height and weight were normal for an American girl of age 4½. I put my stethoscope onto her chest. She was afraid, and lifted it off. I asked Menormelkam to lift his shirt, so I could listen to his heart, and she could see that the exam is painless. That worked. I examined her back, and checked her reflexes.

I pondered her diagnosis: twisted spine, possibly from tuberculosis, possibly a congenital deformity. She has more of a curve, TB tends to cause a pure V-shape. She requires better x-rays, as well as an MRI. She is poorly nourished and needs good nutrition, plus iodine, vitamin A and deworming. And her height is very low, she may have growth hormone deficiency, as does one of my own kids.

"Listen," I said, "I can't promise anything, except that I'll try to get her help. She needs tests that can only be done in Addis Ababa. And she needs better nutrition. I'll find a place for her to live."

I handed Menormelkam 300 birr, $33, a small fortune. I gave him my phone number, and told him to call me when they arrive at the bus station in Addis Ababa.

He explained that if he's going to bring her to Addis Ababa, he needs to tell her grandparents. They'll return to their village in the morning. He turned to Selenat and said "if it's G-d's will, Zemenework will be cured."

The timing was fortuitous; the filmmakers had a day off, so they rented a jeep, brought Zemenework and Menormelkam to their village, and filmed the discussions.

Tesh said to me "Rick, this is a miracle." Selenat said "it's unbelievable, it's more than a miracle." Menormelkam said "you are an angel, sent here to help us. "I'm happy to help," I said, "but I'm no angel." We laughed.

However, of the 80 million people in Ethiopia, I believe I'm the only person who could possibly assist Zemenework. I should not have been in Gondar on Wednesday; I was there only because I extended my trip. When we talked about the details of our whereabouts that week, there just a 15 second window for us to meet - the 20-step walk between Delicious Pastry and Golden Internet. Tilahun’s lateness caused me to step out far-later than I had planned. That encounter changed Zemenework’s life.

Watching the TV news later that night, I saw that our meeting took place on the 10th anniversary of Mother Teresa's death. I'll bet she's smiling at us.

Next week I’ll give you followup, so stay tuned!

~Story and photo told with permission of Zemenework.